The site of almost all social work is the family. Especially in child protection, families are where we find many of the causes of, and solutions to, the problems we try to help solve.

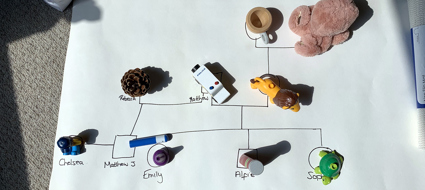

To navigate these families, we often find ourselves in need of a map. The genogram has become a key tool for building this map and communicating it to other professionals. Going further than a family tree, a genogram contains relational, cultural, and historical information to reveal patterns, exceptions, and resources that otherwise would be invisible to professionals until stumbled upon. The genogram can also be a therapeutic tool, helping families to see patterns on paper that are harder to detect when lived.

The genogram has its origin in social research in the 1950s and 1960s and was adopted by other professions through the 1970s and 1980s. The genogram conferences through the 1980s standardised the symbology, and some voices from that era continue to insist on a single set of symbols to be applied to all families. This view sees the genogram as more of a tool of social recording, with the highest context of gathering information and consistently transmitting it between professionals.

However, as the genogram’s use as a therapeutic tool has spread, some of these orthodoxies have broken down. During my social work and family therapy training, I remember being encouraged to come up with my own symbols for concepts and patterns that either did not have established symbols, or when (to be frank) I couldn’t remember the official ones. Working with sensitive topics such as substance misuse, incarceration, and death also require a degree of flexibility in symbology.

The traditional method of showing a deceased family member is to draw a cross through their circle or square, which can, of course, cause significant distress for the family members in the session. I recall working with an eight-year-old boy, whose sister had sadly died of cancer some years before. He had included hobbies and toys special to him on the genogram in blue, and we agreed to write his sister’s name in blue as well, as a way of acknowledging that she had passed away while also honouring how important she was to him.

There is a long tradition of adding further symbology to the basic structure of the genogram. Hardy and Laszloffy invite trainees to show their culture(s) of origin, while Dee Watts-Jones shows us how to question the assumption that care always follows a biological structure by asking the question 'who raised you' rather than 'who is your mother'. However, broadly speaking, these flexibilities have not questioned two fundamental aspects of the genogram: that peoples are shown relationally (with relationship lines between each other), and that they are identified by gender (using a circle for women, and squares for men). Almost universally, without a gender and a relationship, you cannot be shown on a genogram.

When constructing a genogram, I tend to find myself establishing and recording who is in the family, and then filling in the other information: patterns, details, and social graces. I found myself wondering what would happen if we moved gender from something that was needed for a person to exist on a genogram, to this second phase, when other information is collected. This has the benefit of minimising assumptions based on names or heteronormative assumptions, and not signalling to the family that gender is something we are exclusively focused on; instead, relationships take sole position in centre stage.

By using the same symbol for everyone, and then recording gender subsequently through pronouns or other indicators, the emphasis of the genogram session is changed, and a new curiosity about gender becomes possible. I hope that this might lead to a broader spirit of flexibility and curiosity when it comes to assumptions hidden in how we approach the genogram.

An updated Practice Tool explores the use of symbols, the concept of gender privilege in the construction of a genogram, and how genograms can be used in social care and family proceedings.