Discussing the use of generative AI in children’s social care case recording

Published:

The emerging use of Generative AI (GenAI) is changing the way social workers produce case recordings and make use of information. There are many benefits to using generative AI, such as saving time and reducing administrative burden, however, these benefits come with risks and ethical challenges.

These resources were developed by the Children’s Information Project Learning Network, which is funded by the Nuffield Strategic Fund and hosted by the University of Oxford in partnership with the University of Sussex, the London School of Economics and four Local Authority partners.

Introduction

GenAI is a form of artificial intelligence capable of producing new content, including text, images, or music. GenAI generates content from inputs provided in natural language, voice, or stored data. GenAI is the most common type of AI used in social work. It is used to generate case notes, correspondence, meeting minutes, and other case recordings and administrative tasks.

These resources provide an overview of how we can make better use of GenAI in our work.

How Generative AI is being used within social care organisations

Research in Practice and the Children’s Information Project hosted an open invitation webinar that focused on:

- The opportunities, risks and ethical challenges of using generative AI in social work case recording, and

- How we can make better use of information to improve outcomes for children and families.

Our webinar hosted 361 social workers, practice supervisors, practice leaders, and local authority employees with quality assurance responsibilities and data expertise.

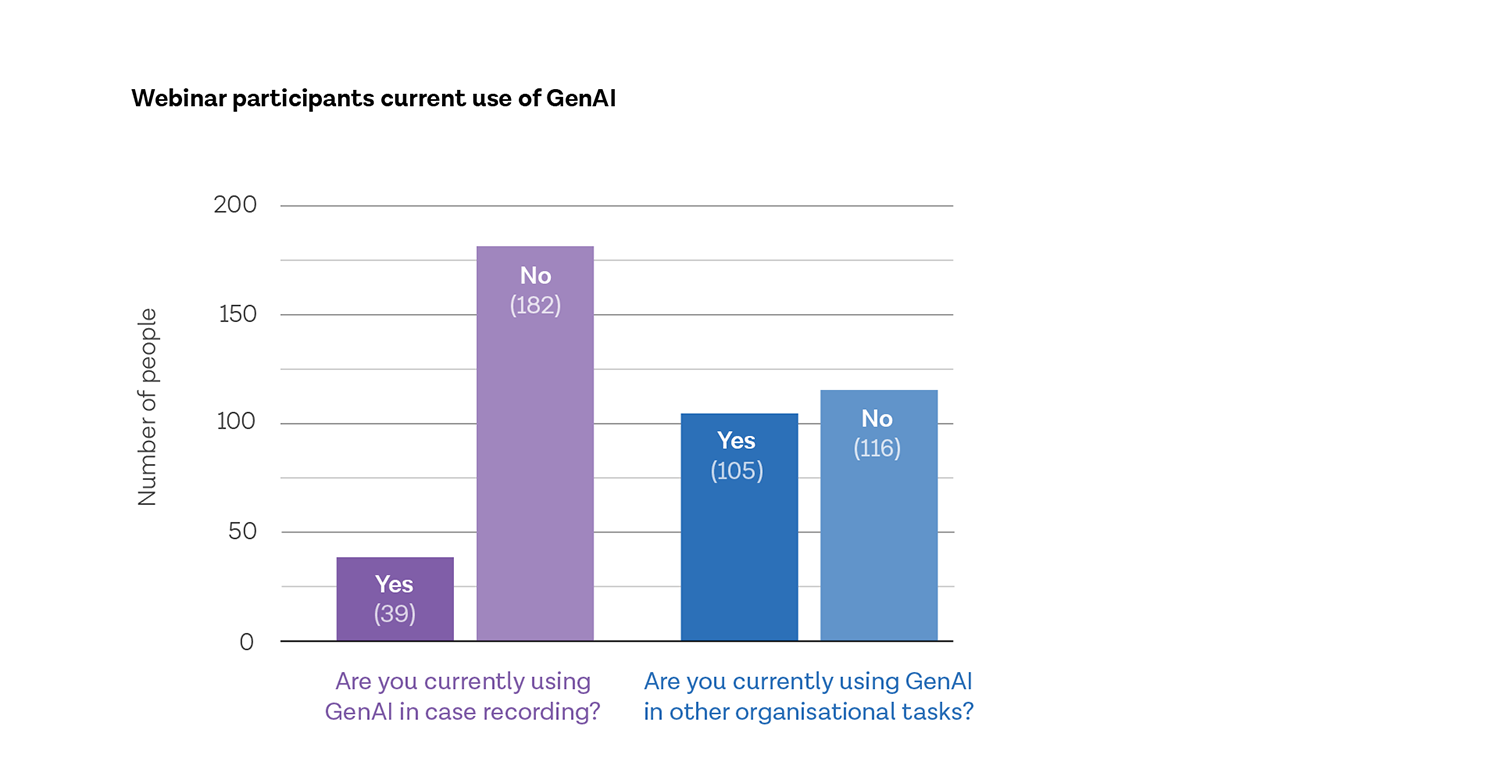

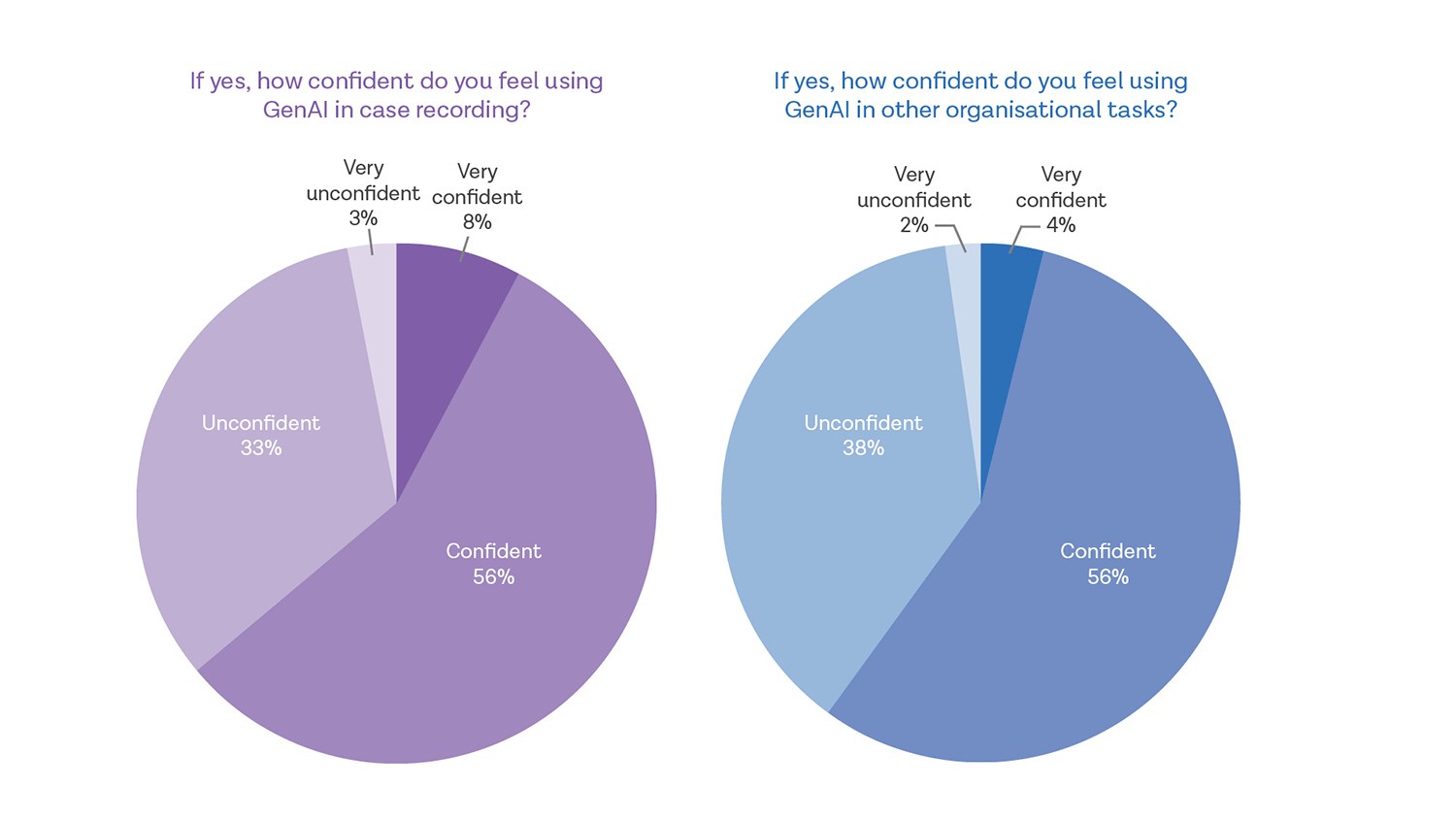

A poll was taken during the webinar which showed that participants had a mix of expertise in using generative AI in case recording and other organisational tasks. Of the responses, only 39 participants were currently using generative AI for case recording and 64% (25) felt confident or very confident using this technology.

Of the 221 responses, 105 are currently using generative AI for other organisational tasks and 60% (63) felt confident or very confident using this technology. While it is positive that there are confident GenAI users, it also shows that 40% (88) of people using GenAI in other organisational tasks and around a third of people using GenAI in case recording feel unconfident or very unconfident using the technology.

GenAI in case recording

Talking Points

This video shares:

-

What GenAI is.

-

How it can be used in case recording.

-

The influence of GenAI on voice and children's information.

[Intro]

Sarah: Welcome to the Research in Practice podcast for the Children's Information Project. In today's podcast, we discuss the use of Generative AI in case recording in social work. Generative AI refers to artificial intelligence systems that can create new content such as text, images or audio. It does this by learning patterns from existing data. These models can generate outputs that resemble human creativity and expression, offering innovative tools for a wide range of tasks. The emerging use of Generative AI, or GenAI, is changing the way social workers produce case recordings. For example, social workers are using GenAI to produce case notes and meeting minutes from voice recordings, or to analyse and synthesise information. Using GenAI in case recordings has many potential benefits and offers an opportunity to reduce administrative burden for social workers. However, it also comes with risks and ethical challenges.

On 17 July 2025, Research in Practice hosted an open invitation webinar about using Generative AI in case recording. There was an overwhelming response to the webinar, which indicates the level of interest in AI. The webinar concluded with a panel discussion that explored a range of things. This podcast captures the panel discussion. Sophie Woodhead from the National Children's Bureau facilitated a discussion between Mark Peterson, the Head of Data and Insight from North Yorkshire, Mairi-Anne MacDonald, the Deputy Director of Development and Innovation at Research in Practice, and Sarah Rothera, a Research in Practice Associate. The panel responded to a range of questions and comments from participants, including themes around the lawful, ethical and responsible use of AI, the influence of Generative AI on voice and children's information, the impact of AI on critical thinking and professional development, and we also explored the importance of AI literacy, and roles and responsibilities in AI implementation. Now, let's tune in as Sophie begins the panel discussion.

Sophie: We'll, kind of, go round the room of panellists, and ask some specific questions, but we'll be focusing on roles and responsibilities, voice and AI literacy. I've noticed in the chat that there have been a lot of questions relating to the use of this information in a court setting, so we will attempt to respond to that in the course of some of these responses, and we'll be pulling some direct questions as well, from the chat. But I'll start off generally, and also, perhaps invite Mairi-Anne to come in an introduce yourself, and perhaps share some perspectives on what's the driver here, for integrating AI into social work, and specifically case recording.

[Integrating AI into case recording]

Mairi-Anne: Thanks very much Sophie, and lovely to be here today, and to hear from everybody in the chat. I think we can tell by the number of people who have come along today that it's a topic that's really interesting to everybody, and we all want to find out more about it, and that's part of the problem. Part of the problem is that there's so much that AI can offer, that we all want to do it, and we all want to do it now, and so sometimes, that means that we don't necessarily make considered decisions about how, when and why we should use AI. And just really reflecting on the use of AI in terms of voice, it's really important to understand the dual nature of a case record. So, part of it is around that organisation responsibility, and your professional responsibility, to accurately record your interaction with a family, but the other really important purpose of the case record is to provide a record to the child of their experience in care, or while having worked with a social worker, or someone in the social care team. And if we think about it from that perspective, we need to be really careful about how we are making sure that the child's voice is authentically recorded and used, so that the child actually can then find their record. Now, you can argue that, 'Ok, well, you know, when someone writes a case record, they're actually also translating what somebody says into a paper or electronic copy,' and that's true. But a worker doing that has got an ethical framework for thinking about that, and so, we need to think around, is there an ethical framework in place for decision making around the use of AI in case recording, and how is that applied? And at the moment, each local authority does that on their own. They have their own policies in place, and they apply their own policy with differing amounts of requirement for consent, for how they use that, and for the transparency around it.

So, there is something, I think, about how we have something that is much more transparent, much more rational, and that actually, rather than just rushing to use all of our own things, we actually have some underpinning decision making, ethical decision making framework, that really supports that across all the local authorities, and the use of AI more generally. I think that one of the important issues that's been raised in the chat is actually, how do we let people know that AI is being used? Do we have an ethical responsibility to do that? I would say yes, and how do we do that, and do we do that with any consistency? Do social workers, or social care workers, know enough about the use of AI in their systems to be able to confidently explain that to people, and if we have AI built into our system, and somebody says, 'No, I don't give my permission for my data to be used in that way,' do we have any recourse to actually say, 'Ok then, that's fine, we'll agree with that, and we'll not use that for your data,' and I expect that we don't. I think once we start using AI in a system, it's used across the whole system and it's difficult to, kind of, walk back from that at all. So, that ethical framework is really important, and the ethical framework means that it provides a basis for decision making, rather than thinking about, 'Well, is Copilot better than Magic Notes?' Because relying on, or thinking about, the software itself, is not going to be helpful. It's changing so quickly that making recommendations about specific software isn't going to help your organisation in six months' time. Thinking around how we make decisions, and what we need to take into account when we make decisions about the use of AI, provides a much stronger framework, that's really going to support that.

And I think, you know, we've talked a little bit about user voice there, and the other important voice in here is practitioner voice, and just balancing both of these is important. Generally speaking, the use of AI is argued to be helpful to the worker, because it can increase time to be used with direct work with children, it can decrease time to be used on admin tasks. What we don't also have, though, is what are the benefits for children and families, so how do we understand that? And I think that relying on generic systems that you buy off the shelf actually is not particularly safe, and we need to be thinking far more around how we can use bespoke systems, and generate bespoke systems and requirements, so that we can make sure that we've got an ethical use of AI in practice across the whole of social care. And if we're thinking about practitioner voice as well, we also need to think around, how are we preparing the workforce for the future? What are the new skills that people need? What is the new knowledge that people need to be confident and competent in terms of both understanding how AI is used in the system, and what difference it's making to the data that's being put into the system, but also how they explain that to people in a way that they can make confident decisions about whether their data can be used by AI. And I think we also need to recognise that AI does change things, and so, you know, just to use another example, how many of you can do mental calculations without a calculator? I would probably say not many, whereas my parents can do quite complex mental calculations in their heads, because that's the way they were brought up. So, there's something around the familiarity and the ongoing use of AI that might affect some of the skills that we currently use in social care practice. One of these is critical thinking, and so, there is some evidence coming out of the research and, you know, as Sarah said earlier, all of this is under researched, and we need to do a lot more to find out what we need to understand in the future.

But some of the research is suggesting that critical thinking skills are reduced, because AI means that there's less opportunity to practice critical thinking, because AI is doing some of that thinking for you. And so, we need to understand that, particularly in terms of social work practice, where critical thinking is such an important part of assessment and professional practice. So, if we are using critical thinking less, how does that then impact on people who are new in career, new into the profession, and how does it impact on people who are more experienced, but using it less? So, what are the other opportunities we can provide to practice critical thinking and the other essential skills, if we're not going to be doing that through the use of case recording. However, the point that Mark made, the point that Sarah made, and that is reflected in the chat as well, is that even if we are using AI in aspects of social work practice, that does not take away your professional responsibility. If you're a registered social worker, you've got professional and ethical responsibility to be responsible for the work that you produce. And even if AI has been part of that, and you could argue that the minute you look something up on Google, AI is part of that. So, if AI is part of that, that does not negate your professional responsibility. So, if you're going into court with a report where AI has been used to generate some of it, you are responsible for that report. You can't say it was AI that did it, and there was a mistake in it, you're responsible for checking and having oversight, etcetera.

So, there's something also around thinking about how work will change. So, while we will retain our, kind of, key professional tasks, some of the details of how we undertake these tasks might change, but making these changes in a considered way, that considers both the ethics, the professional responsibility, and our responsibility primarily to the children and families that we're working with, about making sure that their voice is authentically recorded, and is a clear and honest representation of their voice, is really important. And I'm going to stop there, but I can come back to any specific questions, because I've talked for quite a bit there.

Sophie: Thank you, Mairi-Anne. Yes, that was really interesting to specifically, kind of, consider this in the context of the benefits for children and families. But also, to be touching on those points that are clearly at the top of people's minds around critical thinking, around practice, around professional responsibility, and linking that, and having the interface with an ethical framework to really support that but never losing sight of that professional responsibility. At the moment, what we're thinking and seeing is around how those tasks might be implemented or changed, but that level of professional responsibility remains the same. And I'll just pull in a question that's linked before I go to the other panellists, from Jessica Garner in the chat, who's thinking about the role of social work education with these changes in mind, and is there any advice or any thinking around embedding the use of the ethical frameworks into curriculum, to adequately prepare social work students for practice?

[How might AI change social work education?]

Mairi-Anne: Well, what an interesting question, I'm glad you asked that, Jessica. So, Sarah and I have recently been working with Social Work England to have a think about how the use of AI might impact on social work education, and while we can't share much in the way of findings from that at the moment, that report is expected to be published later this month. And so, look out for that, but I think in general terms, there are people who are using AI in social work education at the moment, and it's a bit like practice, it is happening in some places and not in others. And so, institutions who are more interested in it, and who are thinking about it more, are tending to use it more, and to be also thinking around, what do they need to add into the curriculum for students about the use of AI. But one of the complications that is coming out of that is that, because it's happening in different ways in different places, it can be quite difficult for students to know what to do, for when they go on placement in particular.

Sophie: Thank you so much, Mairi-Anne, that's fantastic, and there is a point on critical thinking, I think, that's going to come up, and I'll come back to it, actually, because I'd like to invite Mark in now, at this point, to think about the overall purpose and driver, but also in terms of roles and responsibilities. What encourages, from the experience that you've had in North Yorkshire, the responsible decision making, and also leadership in the use of Generative AI for case recording?

[What encourages responsible decision making?]

Mark: I think on the first part of that, there's an obvious thing from a local authority, we were always asked to do more with less. So, it's how can we use the things that we have, the things that are coming along, to try and allow us to try and bridge some of that gap. We know that demand increases, and the resource does not align to demand, so there is that challenge. We know that the data that we've got is probably locked away, in a way that doesn't allow us to use it in the most effective way. AI potentially creates an opportunity, as we have shown with the knowledge mining. And the other part of it is that some of this is done to us. So, suppliers are going to embed AI within their solutions. So, whilst the examples that I've shown are things that North Yorkshire have actively gone out and decided to do, other things just happen. So, if you think about your streaming services, the fact that it's doing AI-generated recommendations of content to watch next in the background, you probably didn't read the end user license agreement when they changed it and they sent the notification, but they just put it into the platform, it just happens now. So, there is a changing landscape that we can either bury our heads in the sand, or we have to engage with, and understand, and think about how we approach that. Interestingly, DSIT was mentioned earlier, Department of Science, Innovation and Technology, and they are currently advertising for board members for a panel around AI ethics. So, central gov are looking to get people from different sectors involved in that conversation. There is an all-party parliamentary group around AI and how we use that, and what's the right approach as ethical considerations.

So, there is lots of stuff in their space, and even, actually, Meta, who are the big, obviously, evil, dominating world leaders, they run a programme called Open Loop, and Open Loop is looking at how we can ethically govern and be transparent around things like foundational models. So, they're the model that sits right at the very bottom, that all of the other things are built up on top of. So, there's a really important bit in there, that actually, ethics is at the forefront of this, and thinking about how we do this, but being aware that it's coming, and in a lot of places, it's already here. So, I think that's, kind of, the backdrop. In terms of the roles and responsibilities, it's an extension of that. I think leadership understanding that concept, that the technology is here and we have to leverage it appropriately, but there is value. That's different levels of value in different places, and different levels of value for different people, but it's an awareness that there are tools, and I do think of them as tools, to be able to solve potentially part of the problem. So, if you start with the outcome rather than thinking about the technology, the whole solution to that outcome is unlikely to be AI. There will be lots of different components, and AI might be one of those. I think the other thing that we've probably slightly done as a disservice to ourselves, because the buzz phrase that gets used is, 'Human in the loop,' and, 'Human in the loop,' makes it feel like we're just part of the machine, and we're not just part of the machine. So, one of the phrases that we've tried to use at North Yorkshire is, 'Human in the lead,' we've changed one word, but it massively changes the context of the statement, which is, 'You're in charge, you're accountable for this, you're responsible for this, this is on you, and you can use this, and it is valuable in certain places, but this does not replace you. You absolutely have to own this, and use it where it feels right.'

Sophie: Thank you so much, Mark, and I think that, 'Human in the lead,' is certainly a much better framing. An interesting question around, kind of, linked to roles and responsibilities, Mark, and the changing landscape that you referred to - we're all recognising that this is a very dynamic and changing space. So, if we still need research in certain areas, why would we proceed towards implementation?

Mark: It's exactly why we started with an AI ethics impact assessment, because we had to start with, 'Is this the right thing to do?' And in some cases, it isn't. There was a large tech company that created a model that was designed to analyse CVs, and they trained it on historical information, and it was a tech company, and surprise surprise, historically, tech companies were slanted towards male employees, so it started selecting all of the male employees. Absolutely not acceptable. So, there are things in there, that just because you can do something, it doesn't mean that you should do it. The important bit comes back to a point I made previously during the presentation, I think it comes down to risk and value. We have to accept that it is not 100 percent right, but people are also not 100 percent right, and if it can provide value that is greater than its risk, then it's something that you might start to consider. It doesn't mean you definitely need to say yes, it's not, kind of, 'It gets to 51 percent, and then we're definitely doing it,' but it's those types of things where we have to start to look at some of these things. Because they are out there, and actually, if it gave 80 percent of value, or 90 percent of value, even though it's not 100 percent, it's still something we need to have on our radars.

Sophie: Thank you so much, Mark, for that really thoughtful response. Sarah, I'd like to bring you in. There are many more questions in the chat related, kind of, to that point, but also to the point of levels of surveillance, and that linking of information in the advanced way, the linking of information and the adverse effects of that, which we might consider a little bit later. But Sarah, to the point around AI literacy, and again, we've touched on this a bit around professional responsibility, maybe training, but it would be really interesting to hear what considerations or support might professionals need to build in confidence or critical understanding of AI.

[AI literacy]

Sarah: I think the question of AI literacy is central to everything that we're talking about, because I'm a little bit glass half empty on this. So, when I look at the poll results from earlier, I see that we've got quite a big audience today, and we've got 39 people who are using AI in case recording, but only around half of them feel confident in using it in that way. So, being glass half empty, that tells me that there are a lot of people who do not feel confident with using GenAI, but it's being used, whether that's with their employer's consent or not. So, I think we have to really keep the question of AI literacy central in all of our planning and purchasing, and use of AI, and to me, there are two learning curves. So, when you introduce the product, there's the learning curve of learning how to use the product. AI is actually quite intuitive, so quite often, that learning curve is much lower for people, which I think can give a false sense of confidence, and I've worked with social workers on a whole range of different projects over the years, around data, and that have involved IT [information technology] and different ways of being efficient, and all of those sorts of things. And I've found that, you know, people have, obviously, different levels of understanding and capabilities with technology, but I've found with AI, that's reduced quite significantly, because it is so intuitive, which I think does create that false sense of confidence. And the other part of that learning curve is not just learning how to use the application, but learning how to use it lawfully, ethically and responsibly. And I think that when we're looking at that AI literacy journey, it certainly does start in education and training, because the questions and Mairi-Anne's response have touched on this a little bit already.

So, this is not just around, how do we make sure that social workers are using it, and maintaining those professional skills, but what does that actually mean for social work students? You know, how can we actually refit things so that they are actually getting the education that they need to be able to do this? And I should define AI literacy as well, because it refers to the skills, knowledge and critical thinking needed to understand what artificial intelligence is, and to recognise what it can and can't do. Knowing what it can't do is absolutely central to this, and I know I'm, sort of, reiterating some of my points here, but I just really want to make sure that there are some takeaways here. You know, to give you an example, because I've noticed in the chat, there's been a really strong theme around court, and that's a really good scenario for us to think a little bit more about. Because let's imagine a social worker has used Generative AI, produced a lot of case notes, there are also other forms of AI being involved in the system. When you get to court, the level of accountability that we experience just escalates. You might have a family member who is not feeling good about the intervention that they've had with social care. What does this mean for the trust that they have in the information that is within those case notes? What does it mean for the trust in the reports, and the chronologies, and all of those sorts of things? So, this does have real life implications if we get it wrong. Can the social worker speak to the way that AI has been involved in decision making? Can the social worker speak to the quality and the accuracy of what's written in the reports, bearing in mind that cases transfer from social worker to social worker at times?

So, it does raise real life ethical concerns that we need to be mindful of and, you know, to me, this comes back to, to refocus on your question there, Sophie, what support might professionals need to build that confidence and critical thinking. To me, it comes back to having really good quality assurance procedures in place, so making sure that there's a lot of work invested into what that actually looks like at an organisational and team level, because I think that it is quite contextual. Thinking about what AI literacy looks like within your specific context, because it's going to mean different things for different teams and different people, and also for different applications that you're using. But it's also developing the skills and knowledge, so understanding that if you can craft a prompt, you can craft prompts in all kinds of different ways - some are better, and some are worse. So, helping people to, sort of, develop those skills around prompt engineering, thinking about what actually retrieves a better result, but also thinking about what that verification process looks like, and I think the business case for AI often lands in the space of 'It's going to save us time, it's going to save us money, it's going to mean that we're going to end up spending more time with children and families.' And I'm quite sceptical about those claims, because I think, yes, it does save time, it certainly saves cognitive load, but we've heard already that that could come at a cost. But also, a lot of that time that you save gets redirected into the verification and validation process. So, for example, if you have a generated chronology that is going to into court, every single line of that chronology needs to be verified against what is written in the case files.

So, you start to, sort of, see how, yes, there are time savings, but there are also redirections, and that net time saving has a little bit of a question mark around it, for me. I think it's one thing for a social worker to verify what they've just heard in a visit or a meeting, I think that's a much quicker, much simpler process and time saver. But when you get into those more complex reports and documents, I think the verification process is actually quite time consuming. I sound very pessimistic, I'm actually very optimistic about the transformative potential of AI in social work. I think that it can help us with our work, it can solve a lot of problems, but the way that we use it is absolutely critical, and that comes from AI literacy. If you're very trusting of AI, which I encourage you not to be, then you're not necessarily going to invest as much time in the verification of the outputs, and that's something that came from that research I was talking about with Microsoft and Carnegie Mellon. So, your level of trust in AI is what triggers your critical thinking skills. If you're very trusting of it, it doesn't necessarily trigger them. If you're not very trusting, it will. And I noticed as well, there were some questions in the chat around people's consent, and to me, this is not just a question about AI. This just goes back to normal processes of consent. We don't record people unless they consent, that consent is informed, that consent is freely given, and I think that they're just general principles that we apply to any part of our social work. I just wanted to finish on that.

[Monitoring of information and consent]

Sophie: That's brilliant Sarah, thank you, and that does talk to that point a couple of people have mentioned in the Q and A [question and answer] around the linking of information, and whether families are aware, and how that information is then going to be linked, joined together, and therefore the, kind of, ongoing effects of that. So, is there anything in the context, whilst, indeed, consent is an issue regardless of AI and, kind of, with AI as well, so is there any other thinking from the panel around that informed process, when we're considering, now, integrating different intelligence to be able to link information? And there was a question there, as I mentioned previously, about that feeling of surveillance and, kind of, much closer monitoring of that information when we're thinking of it in terms of, probably most specifically, geographic monitoring, and others as well, networks too. Any comments first from you, Sarah, and then perhaps over to you Mark, if you have anything to share on that.

Sarah: The question of surveillance, probably, is not so much around Generative AI, but to me, that really comes in when you're thinking about predictive analytics and those sorts of things. I think there's a natural amount of suspicion when it comes to AI. I think we've all been conditioned, you know, by the movies, around not trusting AI and what it can potentially do. But there are legitimate fears in there, I think that there's potential for us to message around AI in a way that is potentially helpful, and potentially harmful. So, we can talk about AI being able to free up parts of our time, we can talk about it with children and families around, you know, this is actually a really helpful tool that can help us to understand really complex problems. But likewise, it can be perceived as something quite scary, not just for children and families, but for social workers as well - because there's a question of surveillance around, well, what does this mean for surveilling social workers in their jobs? Does this mean that we're going to be looking at the way that they're working and spending their time in different ways because we have that analytical capability? So, I think that there are questions of surveillance that we need to be mindful of, within the organisation as well as our work with children and families too.

Sophie: Thank you Sarah, thank you for that, and Mark, any reflections from your side on that point?

Mark: So, I'll try and give the other side of the fence, because I would absolutely reflect all the comments that Sarah's just made. I think there's an interesting thing, that people sometimes have a different perception to what our internal perception is. So, every now and again, we'll get the comment of, 'Well, I just assumed you were doing that with it anyway,' and we almost have this assumption that we are going to do something that somebody didn't like, and actually, when you speak to people, we actually find out that they just assumed that we were doing it, and actually, they wonder why we're not. Because they can see the value in us doing it, and we take the significantly cautious approach in terms of doing things. It's interesting, when we look at people's information, if you think about all of the information that social media harvests from an individual, their mobile phone harvests from an individual, we give away huge quantities of information, which are absolutely monetised, and are not for social good. So, as I say, I would absolutely reflect all of the concerns and caution that Sarah's highlighted, but I think there is also something about trying to understand some of the younger generations, and their perception of the world, and the fact that they've grown up, and that this is literally just part of what their experience is, and how they live. And it's to some degree, possibly scarily so, normalised - that actually, maybe there is a little bit of space where we need to be a little bit more aspirational with some of this. Because there is, kind of, already a presumption that we're doing it. So, just, kind of, trying to give both sides of that fence.

[Can social workers opt out?]

Sophie: Yes, and I think that was really helpful actually, Mark, to think about it through that specific lens, because absolutely, you're completely right there, so thank you for that. Mairi-Anne, coming back and, kind of, pulling us back into the discussion around practice, a lot of questions around the critical thinking, as we've talked about, but I just wanted to pull out a question from Samantha here, which says, 'What if you don't want to use AI? Can social workers opt out of using it?’ They might have concerns about the ethical, environmental and social effects, which are huge. So just any reflections on that, and on practice, and what that, kind of, decision making might mean?

Mairi-Anne: Thanks Sophie, and thanks for the question, Samantha. So, before I talk about social care, let's just talk about general real life, and, you know, AI is absolutely embedded into the systems and processes we use all the time, right now. If you want to not use that, then you probably would have to not use any technology at all, because it is there. Whether you're aware of it or not, it's underpinning a lot of the transactions, a lot of the search functions, you know, all of the chatbots that you see on different webpages. So, AI is in lots of places at the moment. Can you withdraw from it if it's built into a system? I think… unlikely that you'd be able to say 'Well, actually, I don't want to use that.' And you know, just picking up the point that Amanda made in the chat earlier, why are we rushing headlong into the use of AI when actually, social work and social care has been slow in rushing into anything new in the past? So, why are we rushing into the use of AI without actually having a full consideration of the implications of it? And I think that while the consideration of these implications is happening in different places, it tends to be local authority based rather than having a broader, national discussion about it. So, for me, it's very much around that national discussion, about the, kind of, ethical framework for decision making around that. But, you know, in response to Sam's question, I think it's very unlikely that if your local authority has a system that is AI enabled, that you would be able to say, 'Actually, I don't want to use this,' and that would be ok. I don't know, Mark, would you have a view about that from a systems perspective?

Mark: I think you might have that choice now, I think we absolutely won't have that choice moving forwards, and that won't be something that will be of our doing. I think it will be suppliers will embed AI within solutions, if they haven't done already. We will either accept it or we won't accept it, but I don't think there will be an alternative at a certain point in time. But I don't necessarily see that as a bad thing, I think it's as long as you use it in the right way, is the critical piece of it.

Mairi-Anne: And I think, I mean, the bigger issue for me is the consent of people using services, because if the case recording is a reflection of their voice, or should be a reflection of their voice, then I do think they have the right to make a decision about how that's reflected in the case record, and to also think about the authenticity of that. So, for me, the big ethical question is around the use of service user data.

Sophie: Absolutely. There was a point in what you were saying there Mairi-Anne, that I'll just pull out a quote from Megan in the chat, which is just a statement rather than a question, 'Social work is so behind with the use of technology. We need to invest in research, development, and roll out of what would support the recording heavy requirements of social work.' So yes, thank you for that viewpoint, Megan. And I think that also, talking to the fact that AI is so prolific, so everywhere, Shannon states that, 'I've had what I believe is a significant increase in communication from parents and families that appear to be AI generated.' Like you said, AI has a voice, and it's often very evident that it has been used, and so, whilst there's a, kind of, full awareness of the positive nature of the fact that AI has given people from every background, and education and opportunity to communicate and express themselves, there is that pattern of AI use that's really prolific across all aspects and areas of life. There is one point that has come up in a few different places, and once directly, which is around the environmental impact. Before we wrap up and move to the close, any reflections from the panellists about that environmental impact?

Mark: Absolutely, the sustainability element of how we use AI is one of the key considerations that we need to think about. People quite often focus around energy consumption, water is hugely consumed by processing in AI as well. If we look at the usage that we're talking about, within the area that we are doing it, there is definitely an ethical view around what is right. So, I joked earlier, if I used the AI to create me the Olympic diving cats, is that really an ethical use? How much processing and computing are being used to achieve that? If we're using it to support a social worker to keep a vulnerable individual safe, then that absolutely feels like the right sort of thing to do. In the background, you do obviously have the big cloud providers, [who] are trying to create more efficient computer chips and those sorts of things. They're working to net zero and, you know, use of renewables. So, there is a reducing cost. In certain instances, it comes down. But there is absolutely human responsibility about how we appropriately apply it, and where we use it.

[Takeaways]

Sophie: Thank you, Mark. Ok, I will pull the panel to a close, but just, is there one… just a few takeaways from yourself, or one takeaway, if you wanted to give the audience, as we do close the panel?

Mairi-Anne: Thanks Sophie. I hope that everybody's enjoyed the panel today, I certainly enjoyed looking at the chat and seeing everybody's comments and views, and certainly, lots of rich conversation there. In terms of takeaway, sorry, I have more than one thing - of course! And the first takeaway is that AI is here, it's here to stay, and it's how we use it that's where we have choice now. It's not whether we use it or not, really. But the, kind of, three things that I would really be emphasising is, remember the dual purpose of the case record, remember that the fundamental purpose of it is to record the child's voice. So, we need to do that with authenticity. And our professional responsibility is to do that in an ethical way, and that needs to drive the decision making. And I think the second thing is that using AI doesn't reduce that professional and ethical responsibility. It actually means that you have to be responsible for doing that, but I really like Mark's phrase there, about human in the lead rather than human in the loop, so remember, human in the lead, and that's the kind of principle that needs to underpin it. And one of the points that was made in the chat earlier was around whether AI will replace humans in different activities, and I think AI will definitely change the way we work. It won't necessarily replace humans though, but it might change the tasks that we do, and so, we need to make good decisions about where we need human interactivity and where it's the right thing to do, rather than just thinking about, 'Well, it will be more efficient and more effective, so let's just do it that way.' So, these are the, kind of, key points that I would leave you with. So, don't be afraid of AI, embrace it, but understand what you're using it for, when and why.

Sophie: Wonderful, Mairi-Anne, thank you. Sarah, over to you.

Sarah: Yes, my takeaway is around the lawful, ethical and responsible use of AI, and developing your AI literacy, so, for your specific context, so that you're able to do that. And I think that, you know, just to touch on a couple of Mairi-Anne's points there, it is here to stay, we are just scratching the surface of what AI is going to look like in social work. I think that the horse has bolted, and we need to think about what that lawful, ethical and responsible use looks like now, while we're using it for such a narrow part of our work. Because it's likely that it is going to advance out into other areas, like predictive analytics and using machine learning, and all of those sorts of things, a lot more. And it feels like we need to get it right from the start, and to think about what that actually looks like, start our own journeys for developing our AI literacy, and think about what our own responsibilities are within that scenario.

Sophie: Thank you, Sarah, and Mark?

Mark: So, I think I would say, nobody's got the answers, nobody's figured all of this stuff out. AI is absolutely a learning journey for all of us. Some people might be slightly further ahead, but we're all in exactly the same game. So, be curious, go and play with it, don't be scared of it, understand its strengths and its weaknesses, because actually, they are both and it is really important to understand where it's good and where it doesn't help, and be really challenging about that, kind of, appropriateness of where you use it. And as Mairi-Anne said, slightly stole my line, is you are the human in the lead, so make sure that you take that role.

[Outro]

Sophie: A really big thank you to all of you for your time and your participation via the quick Q and A in the conversations, and a massive thank you to Sarah, Mark and Mairi-Anne for presentations and collaboration, discussions in the panel discussion, and a big thank you to Grace as well, for all of the support in setting up this webinar. With that, I think we'll draw the meeting to a close, so thank you so much all, and we've had a great session. Thank you.

Next Gen Social Work

Talking Points

This video explores:

- Perceptions and ethics of Generative AI in social work.

- Examples of how Generative AI can be used in case recording.

[Introduction]

Mark: Brilliant, thanks, Sophie, and good morning, everyone, lovely to have you all here. I'm going to quickly go through a few little bits first and then get into the actual case studies that we've been looking at in North Yorkshire. A little bit of a backdrop that you'll all be aware of, in 2011 there was the Eileen Munro report, and in 2022, Josh MacAlister did his independent review of children's social care. Both of those, kind of, highlighted a challenge around an admin burden on social workers, and that in some instances social workers are spending 80% of their time doing admin and only 20% of doing the really valuable social work. So, we know that there's something that needs to be adjusted in that space, because actually, the social work element of it is really important, and it's how we can use tech to support that. As we were talking about AI [artificial intelligence], the obvious question, I think, is what do you think when someone says 'AI'? And I think for most of you it's probably the Hollywood version.

[Perceptions and ethics of Generative AI in social work]

These are the types of things that you think of when somebody says 'AI'. I won't ask anyone to pick out what generational formula they're looking at, but you get the gist of where we're going. And what's really funny is this isn't just you either. I asked CoPilot to create me a picture of what it thought was AI, and it did exactly the same, it came up with the robot with the really dark, sinister background. So, this is where the perception of AI goes, but actually, if you look at a dictionary definition, I picked the one from Cambridge, it's computer systems that have some of the qualities of people. It doesn't mention anything about suppressing humans, taking over the world, you know, the world domination element, none of that is in there. So, there's a little bit of re-framing. We need to, kind of, forget about Hollywood and think about what is the actual base capabilities of what AI is going to help us with? But as Sarah highlighted earlier, it's not just about the technology itself, it's about the information that we feed into the technology.

So, we like to think of this concept of AI deserts and jungles, and if we think about the data or good data being the water, and the leaves, the foliage, being what we can do with AI, if we don't have any data, if we don't have any really good information, actually, there's not many leaves. It, kind of, looks a bit like a desert in terms of the capabilities we can create. Obviously, in a rainforest we get loads of water, lots of good data, and therefore, we can do lots of good things in an AI space. But I've now also said 'data' about 50 times, so I probably just need to tick off and make sure that we're all on the same page around that too. So, again, I'm not going to keep the score. Keep a mental track in your head and see whether you think yes or no on these ones. So, does this make you think of data? I think most people are probably there, feels quite technical, feels quite numbery, but probably pretty comfortable with that, but what about medical scans of people? Again, a few might waver, but I think we're probably mostly in agreement. This is where it gets interesting.

Now, for the audience here, all of you will be absolutely, 'This is data,' and that is amazing. If I ask other people from other disciplines, they definitely waver on the concept of conversations with people being data, but when we're recording people's lives, their experiences, their relationships, it's absolutely data. And when we know that if the information about an individual ends up in the wrong hands, it can put the physical at harm, we can't separate the concept. So, we have a digital twin of a human, and actually, we need to treat them with the same and love and care and protect both of those. And love and care and protect in data land feels like odd words to use, but they're the right words to use. So, when we thought about the approach that we were going to take from a North Yorkshire perspective, it can't just be about technology. It's this Venn diagram of, yes, technology is important, that's obviously moving, but ethics and practice are just as important, arguably probably more important than the technology piece.

So, they have to be at the forefront, and what that meant was that when North Yorkshire looked at trying to implement some technology in the AI space around children's social care, we, kind of, took this three-prong approach. We looked at assurance, reassurance and then actually just using it, having a go, 'cause until you try and play it, with you're just not quite sure. And in that assurance space, one of the really important things was our ethical impacts assessment. So, you can see here we've got some, kind of, pillars of what's in there, and there's the standard techy things that you would expect to be in there around transparency and governance and robustness and safety. But alongside those are the really important ethical practice considerations, human agency, dignity, fairness, avoiding discrimination. Those types of things are just as important, and what we did was we do a… we do an ethical impact assessment around all of the AI projects to ensure that we've had that robust conversation. And that's not just technology people, that's technology people, ethics people, people in services, you know, practitioners.

[Examples of how Generative AI can be used in case recording]

We get everybody involved in that conversation to make sure it's an open, transparent and challenging conversation, because just because we can do something in a technology space, it doesn't mean we should, and that's always the approach, that's always the decision we've got to make right upfront. So, let's have a little bit of a look at some of the prototypes that we've done. So, we've done a knowledge mining prototype, so this was looking at what we could do to get information out of a children's social care system. Now, why do we need change? Well, I've put down there a few streaming services, gives you, kind of, an idea of how many pieces of content that is literally at the tip of your fingers. You can go and ask your smart speaker for one of 100 million songs, and on YouTube, I've put a little blank there, I'll fill the box in, have a think in your head, was it close to that number? 5.1 billion videos approximately on YouTube. We've only got about eight billion people on the planet, and we've already got 5.1 billion videos on YouTube. That means if you want to watch videos about cats doing Olympic diving, they're absolutely there for you. Whether that's the best use of time, I can't guarantee that, but that's what we experience in private life.

When it comes to keeping children safe, the vast majority of us have this same challenge. There's two large systems, whether it's a Mosaic or whether it's a Liquidlogic, and the information tends to be trapped in these three pots, in case notes, forms and documents. And the question from a North Yorkshire perspective was, 'Could we do something differently here to maybe take some AI, maybe look at that information differently, and see whether we could give a better view of that information?' So, what we came out with was this product here. This is visualised in Power BI, and what we've got at the top there is what we call the Ferris wheel. And basically, if you think about when you, you add information into your social care systems, your case management systems, that's the relationships, the structured relationships, that you have recorded. And that Ferris wheel shows probably a typical number of relationships for an average child. That will be your mum's, your dad's, maybe siblings, grandparents, probably a couple of social workers. There's not a lot of people within that network to be able to keep that child safe when crisis happens.

So, keep that Ferris wheel in mind. We're going to look at some other stuff and come back to it. The other things that we produced in the project was across the top there you can see just a timeline of interactions. Now, to our knowledge, there isn't another local authority in the country that can visualise this, which it seems like a really simple bar chart of, 'How many times have we interacted with an individual over time?' and actually, those interactions, you can see a peak. Was that a crisis point? But more importantly, not only is there a peak there, if you look before that, you can see a couple of increases in interactions. Were they tells, were they occasions, that actually, had we have picked up on them, could we have seen that there was an opportunity to intervene early? Could we have done something differently to avoid that crisis point, or give some sort of better outcome? The bottom part of that is the chronology. I'm sure lots of you have probably had to create chronologies in the past, and they can take days, they can take weeks. They are extremely tedious and not a valuable use of time.

What the tech does is it scans through all of the words ever written about those individuals within those three pots, and it takes that and creates that timeline for you. Now, we found two parts to this. The way that North Yorkshire chronologies, and I'm sure others do, is that if you build a chronology and then you have to build the, the newer version of the chronology, people start from the previous version, and add in from that date. What that means is that, if something was missed in the original chronology, or if some data was added retrospectively to an individual's record, it just gets missed, it never gets added. The technology doesn't do that. The technology scans all of the information and goes and finds that. The other thing that we've got is just pulling out all of that information into one space. So, rather than having to go to all of the individual pots, searching, if it's a document, downloading it, open it and search to see if it's got the information you need, find out it hasn't, search, grab another, download that and search again, this puts all of the information from those three pots in the same space.

And if you want to search for the word 'alcohol', you search for the word 'alcohol' and it finds you all of the references to it. And you can do a highlight on it, so actually, it will pick out where those words are within all of those different pieces of text, so you can see the context around it, because it's not just about finding the information. It's about what else it says, so that becomes really, really important. And where this could potentially go is, if we think about CoPilot, and obviously CoPilot has been mentioned, can it start to become a little bit of a digital assistant? You can ask for summaries across an individual's record, you could start to ask questions like, 'When was the most recent safety plan?' and it will be able to pick the dates out, rather than having to trawl through. So, there's some huge opportunities in this space, but obviously we need to make sure that we're doing it right. So, think back to the Ferris wheel, that, kind of, dot, there was about eight connections around it. We asked the AI to go through and look for anything looked like a person, a place or a product, they call it, which a product could be anything from a toothbrush to drugs and alcohol, and instead of those eight, this is what we got.

We've got a huge network of all of the people that those individuals had ever mentioned. Now, on face value this is, like, 'Oh my God, this is quite scary, look at that diagram,' but actually, when we spoke to social workers, what they said was, 'This is amazing. This is-, this is removing the admin bit of finding the information, and now allowing me to do the social work practice bit of finding out about those individuals, and how they fit into that child's life.' So, this becomes really exciting, and you might only care about a certain point in time, so we put some sliders in there so that you could filter it down to say, 'I only want to know about relationships in the last three years. I only want to know about people, not places.' And really importantly, the bottom slider there on the left that's just been adjusted is what's called a confidence score. So, for an AI, it basically will look at the piece of information and it will decide, based on a probability, whether it thinks Mark Peterson, as two words, is a person.

We went backwards and forwards about whether we should set that at a particular figure and what that right figure would be, and then decided, absolutely no, that's not the right thing to do. Practitioners should be able to control this, they should be able to decide how confident they want the technology to be. If they put it at 100% and there's not very many things on the diagram, well, make it a little bit less certain and you might get a few more, or vice versa. The other really, really important thing that we did in the space is this just tells you about people, it will absolutely not tell you whether that individual is a risk or somebody that can keep that individual safe. So, that is the social worker piece. Where we've used the technology is purely about extracting information to put it into a social worker's hands, so that they can make the informed decisions. It is not about us making AI-generated decisions. The last part within the product, we started to look at place, and place is a really interesting one, 'cause again, you can start to see areas that individuals are going to.

That might give you ideas about relationships, but it also starts to open the door of things like contextual safeguarding. Can we identify a place that one individual mentions is a risk, and that we know is a risk to one individual, and another individual has also mentioned? That's really, really difficult to do cross-records right now, and if we think about that cross-organisation, that's almost impossible to do. So, there's huge opportunities in the space to think about this. We did some click testing, because obviously we wanted to get some metrics around it, so I've just picked out a couple. In terms of safety plans, finding a safety plan is something that gets done on a really, really regular basis. Without the tool, on average it was about three minutes. With the tool it was about fifteen seconds. That's a huge time benefit for something that you're doing on a regular basis, and that's just one task. There was dozens that we checked, and they were all improvements, of varying different degrees, but always an improvement.

The other thing was going back to that point about keeping children in their area, you know, their schools, their social circles, their sports clubs, and around the people - having the people around them that can love and care and protect them, we found up to nine times as many people as we traditionally have recorded without the relationships within systems. That creates a huge potential to try and keep people safe, potentially keep them out of the care system. So, that was one of the products. Next product, Magic Notes, so that's speech to text. Again, this has already, kind of, been touched on, but where we look at it differently, I think, is that we look at is as a capability, so we're not looking at its specifically Magic Notes as a product. It's about how we convert speech into text and how we use that in a recording-, how we use that to record against a child's record. Now, the, that hopefully gives better information. It's a full recording of the, the session that takes place, and it saves some time in terms of getting that information into the case management system. The feedback that we got from this, this type of solution being used is that actually, it's a more engaging conversation.

Social workers felt that they could be more present in it rather than having to concentrate and summarise and write the notes at the same point as they're having the conversation. And off the back of that, it made people feel like they had an improved morale just generally. It, it was, sort of, assisting with people's enjoyment of the job and, and feeling that they were delivering really what they joined the practice to do. So, that's, kind of, a, a quick whizz over that. The last one that I'm going to touch on is a large language model, and we call it Policy Buddy, or Polly for short, and what this was about was taking all of our internal policies, along with the national guidelines, and putting a model across the top so you could ask it questions. So, example here, you're a new social worker, you're going out to do a statutory visit, 'What do I need to consider?' Now, within a few seconds it will tell you how to prep-, how to prep, what you do during the visit, what you need to do after the visit, and if there's any other additional considerations.

Now, that's really useful, because it gives you a quick summary, but also, the other part to it is that people might feel-, 'guilty' is maybe not the right word, but uncomfortable asking the same person the same question, if you're new to social work. Technology has no judgment. You can ask the technology a thousand times the same question, and it will continue to give the answer back. So, particularly a new social-, for new social workers, it gave a real opportunity for them to, to be able to ask questions without feeling any of that kind of judgment. The other part to it, which gets really exciting, is where you can start to tailor it. So, this is an eight-year-old boy, for the review process, but they're really into superheroes. So, what it will do is it will take the process that's really complicated, it will reduce the language or change the language to make it so it's accessible by an eight-year-old, and then it will apply the theme of superheroes across the top. So, you can end up with something that's really tailored and really designed for that individual, that's engagable for that individual, that's super-helpful, but maybe it turns out that that individual's first language isn't English, it's Polish.

Well, again, a short prompt, and all of a sudden you have the same eight-year-old guide about superheroes, but now in Polish. So, there's huge opportunities there to bridge the gap and support individuals in a better way. Just a few comments that we've had, and it's been touched on about neurodivergency. One of my favourite comments that we've had out of all is, 'The AI buddy is a neurodivergent bestie.' I mean, I don't think you can articulate it better than that, sort of, a statement, but yes, its helping people find information, they're thinking about language, writing up case notes faster. The, the comments are continuous. Even one of our social care managers said that they believe it will genuinely improve the mental health of their social care team. That, that-, to be able to use technology in that space genuinely is a huge step forwards. But where do we go next? Now, I know this has been touched on.

The research behind this, this was done in the '60s, so maybe the numbers aren't quite right, but the premise is right in that the amount of communication that we do through the words versus through all of the other means, the tone of voice, the body language and so on and so forth, means that actually, if we think about the really, really rich, valuable conversations that we have with vulnerable people, if we write down words, and I know we try to capture some of the emotional part of that in the words that we use to try and articulate that, we are probably missing something. There is probably more that we could capture, and when we think about voice and capturing that, and how that can then be used to support an individual, there is definitely something in here. So, from a North Yorkshire perspective, where we're thinking is how can you use things like audio recordings and such? The other… the last point that I'll, I'll touch on is this concept of no one system holding the full picture. Now, we have a character, Dorothy, her friends know her as Dotty, and this character basically describes, if you imagine one system, or one small organisation of information, it gives you, kind of, a rough, fuzzy outline of an individual.

But we know that's not right, we know that for most organisations, if they're big ones like local authorities, for example, there'll be lots of information about Dotty across lots of different services. We know that there'll be lots of information throughout central government, health, third and voluntary sector, and actually, we need to think how we get that information in, 'cause maybe if we can bring that information in, we don't get the fuzzy outline of Dotty, we get the full colour version. And actually, if we get the full colour version, hopefully we get a much more holistic view, and we can make better decisions. So, I'll leave it there, thanks for listening, and happy to take any questions.

[Questions]

Sophie: Thank you so much, Mark, that was so much information to, to fit into that short twenty minutes, but there's been a lot of activity on the-, on the Q&A, and it just shows the amount of interest there is, including a colleague from Torbay, who mentions that they're now implementing Policy Buddy after conversations with you.

Mark: Brilliant.

Sophie: So, there were a couple of very specific questions, I think, that I'd put to you first, and then some more general themes that are emerging. The first question was around DPIA, so if you had to do a renewed data protection impact assessment for this, kind of, this piloting approach, and, and what that looked like and what the process was like.

Mark: So, I think picking up the first part of that, when we say 'renew DPIA', I think we just need to be aware that DPIAs aren't a one-and-done. They have to be a living and breathing, and particularly in an AI space, what's happening with the tech and the models behind in the background is changing. So, we need to continually almost challenge ourselves that, 'Are we still doing the right thing, and are things still being processed in an effective way?' So, they're absolutely right to do that. Our ethics impact assessment sits alongside our DPIA. We are potentially looking at whether we blend the two together completely, but obviously we will do data stuff that doesn't involve AI, so there, there is justification for that. But it, it's about that robust rigour challenge. It's difficult from a-, to do anything with AI, you are moving data to somewhere, somewhere else outside of your organisation, normally. There are technical opportunities that cloud providers are giving to try and bring some of that, with the option to run that almost on-premise, but you're generally sending your information to somewhere. However, then you move into the, kind of, data going to be processed in particular regions.

Obviously, we can process data in the UK, that helps to keep things safe, because that brings it under UK law and governance and policy, so it's about thinking about where you process things, and, and as was highlighted earlier, that's some of the challenge around some of these free tools. If you're running things in enterprise environments, you normally have all of your organisational rigour around them. If you are using a free tool, you're absolutely giving your data to that organisation, and they will train it. So, we have models internally where the data that we put in absolutely does not get used to train that model, and that's, kind of, your-, that's what-, that's what you're paying for, and that's where the cost comes.

Sophie: Thank you, Mark, I think that that's really interesting, that talks to some of the-, some more of the questions and concerns around that data security, but just wanted to ask another specific question that came up in the chat about, kind of, quality-checking the, the results, so the chronogram that you presented. What process did you go through in order to, to, kind of, quality-check that chronogram that it had, had developed for you?

Mark: So, part of where we need to get to, there's an interesting challenge. We, kind of, think of technology like a calculator. We think it's absolutely right, and it isn't, because large language models have human-like thought, and human-like thought means that we make mistakes, so the technology makes mistakes. So, we can do… we've done some, kind of… you know, we, you build a genogram, an ecomap, and you can do the same and take the documents, you know, and manually do that. What's interesting, one of the things that we did find is that there's a human trait, which is when we find something we stop. So, if you ask somebody to go and find a piece of information, they'll stop, but there may be another piece of information that is the same as that information somewhere else. The technology doesn't do that. So, we have done some comparisons, and it's okay. For me, AI becomes a really interesting one, because I think it's a risk-value judgment.

So, is it better than what you are doing currently, or is it worse? And I think in most cases, we find that it pulls out more of the information, but it comes back to the original bit about responsibility and practitioner. It is absolutely the responsibility of the practitioner, this is a tool to try and assist, not to replace. So, you always have to approach it with the mindset of, 'This is giving me something, this is giving me some threads, but if I'm not confident that that's giving me enough, then I still need to be going and looking manually.'

Sophie: Fantastic, thank you, and there was also some interest as well from, from someone on the chat to see any documentation, that evaluation of time that you… that you talked about as well in terms of click rates and accessing that information. So, any, kind of, case studies or, or evaluations of that, I think people would be really keen to see it looks like. There were a few questions around the families, young people's response to being recorded. In a few different places, actually, that question has come up, and we might also touch on it during the panel, but was there any specific examples or experiences from the team using it in North Yorkshire and families' responses that you're aware of?

Mark: In relation to using Magic Notes from an audio recording perspective?

Sophie: Yes.

Mark: I don't-, not majorly that's been fed back to me. I mean, I can-, I can check in with colleagues in social care, and, and see whether there is anything specific. I think there will be some hesitancy with everything. It's about how we communicate that message, so fundamentally, if we come from the premise of, 'We're recording you,' it feels very staid. If you come from the perspective of, 'This is a tool that helps us to support to hopefully give you better outcomes,' then actually, it feels like a different conversation. So, I think it's about us being transparent. It's not that we're doing something different. You know, it's, it's supporting a social worker to ensure that those individuals get the best care that we can give them, and it's-, as long as the narrative is right, I think that's maybe we've not had significant resistance to the use of this type of tech.

Sophie: Yes, thank you, Mark. Yes, that's a really-, a really good way to, to consider this specific question. I think one more before we-, before we head over to the panel, if that's okay, Mark. There were some specific questions, again, moving, coming back to that topic of data protection, safety and data breaches. So, just a bit more understanding around given one participant states, 'How are organisations assuring commercial products for use with sensitive data, given the many data breaches and leaks being reported, and in a rights and value-based context?' So, how are we, kind of, thinking of that in terms of the dangers of using commercial products in human services?

Mark: I mean, it's, yes, it's a really difficult question.

Sophie: I know, sorry.

Mark: How do we keep things secure in-, how do we keep things secure in a world where we know that it's very difficult to keep things secure? It, it is always a competition of who is slightly further ahead. I think there's a pragmatism, and the news probably makes people quite aware of this, is that it is almost impossible to keep people's information 100% safe. We will absolutely do everything we possibly can do to do that, and all of the suppliers that you contract with, you know, things like the fact that they are accredited to things like ISO 27001 standards around security, people put absolutely as many measures in as they possibly can do. When you have big threat actors like nation states, it becomes very, very difficult to try and say, hand on heart, 100%, it's secure.

But that's why you have all of your… you know, we have a cyber and infosec team, we do things like penetration testing, you obviously go through accreditations and so on, so forth. Everything is done in a structured way. Within our procurement, obviously we make sure that all of that type of stuff is covered, about the suppliers that we engage with, and yes, there's as many protective measures as you can reasonably put in place, but can you say 100%? I don't think any organisation can.

Sophie: Yes, of course, and I think that, that really clearly, kind of, talks to the point, Mark, about the fact that the, the local systems and structures that already exist within place to be able to support data protection and how those can-, how those are already pivoting towards this consideration and, I think, indeed, to your first point about DPIAs and those being a continuous process, and that we're, kind of, using those structures and supportive structures around the information to be able to ensure to our maximum and best capacity the safety of that… of that really sensitive information. And then just one final specific question again before we go to the panel when we talk a bit more generally, there was a question about the model that underpins AI Buddy. Could you talk to, to that?

Mark: So, it is… the Policy Buddy is provided by a company called Leading AI, so that is a bought-in product from them, and obviously they've taken the national guidelines, and then we provided our local policies, and they've trained the model specifically on that. The other element is that when we talked about that bias, creativity and hallucination, effectively within the model you have the ability to dial down its level of creativity. So, what that means is that you can make it use the information, but very closely follow it, and it won't go off on a tangent and it won't, kind of, be very creative in that space. It will keep itself quite tight and, and close to what the guidelines are saying, but consider that and provide that back in a-, in an understandable, humanistic format.

Sophie: Brilliant, thank you so much, Mark, that was, yes, fantastic, and really great to hear some of those responses as well.

Reflective questions

Here are reflective questions to stimulate conversation and support practice.

- What does AI literacy mean in social work and your specific social work context?

- What opportunities are there for you to use GenAI in your work and how will the use be governed and quality assured?

You could use these questions in a reflective session or talk to a colleague. You can save your reflections and access these in the Research in Practice Your CPD area.