Housing affects so many other parts of our lives

Research links housing with wider wellbeing and there is also an economic advantage in terms of cost-effectiveness. Reflect on how housing and home are fundamental parts of someone’s wellbeing.

What this means

There are really strong associations between physical and mental health, wellbeing, our ability to work and study, and our housing situation. Having home as a secure, comfortable place tailored to our needs is not only ethically important in terms of wellbeing – there is an economic advantage in terms of cost-effectiveness too. It is, in the words of the Living In The Place We Call Home group:

A nailed-on argument for getting this done.

What does living in the place we call home mean to you?

In this clip, David Yeandle reflects on what 'living in the place we call home' means to him:

It is self-evident, but it still has to be said. if you get the housing right, and the right type of housing, then a lot of other things flow from it - including health and wellbeing. You look in all the reports we have discussed, see how much poor housing costs, and you think there must be a way to redirect the money.

How does housing and home have a knock-on effect on other parts of our lives?

Here, Dave Bracher describes how housing and home has a knock on effect on many other parts of people's lives:

The research

There is a large body of research that links housing with wider wellbeing. The risks of poor housing can be physical – including pollutants from mould, building materials, mite allergens, and risks arising from substandard conditions like poor insulation or overcrowding (Wilkie et al., 2018). In 2020, it was estimated that for every £1 spent on improving warmth in the homes of older people, disabled people, or those with a long-term health condition, there is £4 worth of health benefits; and for every £1 spent on falls reduction for older people, there are savings of £7.50 to the health and care sector (Centre for Ageing Better, 2020).

There is also an association between poor housing conditions and mental health. Rautio et al. (2018) found that poor housing quality, lack of green space, noise and air pollution are related to depressive mood, while Hoisington et al. (2019) highlight the positive impact of natural light in the home on mental health.

These issues were brought into sharp focus during COVID-19 as people – particularly those with care and support needs who were shielding – were spending all, or the vast majority of, their time at home (Bocioaga, 2021; Centre for Ageing Better, 2020). Poor quality homes contributed to the scale of the pandemic – conditions such as overcrowding led to increased risk of transmission, and disproportionately affected people who were already more vulnerable to COVID-19 and other health conditions (Centre for Ageing Better, 2020).

However, it’s vital to remember that what people value about home, and what they think contributes to their wellbeing, is personal. The relative importance of different aspects varies from person to person. For instance, Garnham et al., (2021) argue that, because of this, housing organisations need to invest in understanding each tenant and their household at the very start of the housing process, even before they move into a property.

What you can do

If you are in direct practice: Occupational therapists bring enormous value in supporting people with accessible housing and adaptations and thinking about the whole of a person’s life with housing. If you have an occupational therapist in your team, consider speaking with them about how you can link up housing and wider wellbeing.

If you are an occupational therapist, how can you further support colleagues in thinking creatively about how housing and home are fundamental parts of someone’s wellbeing?

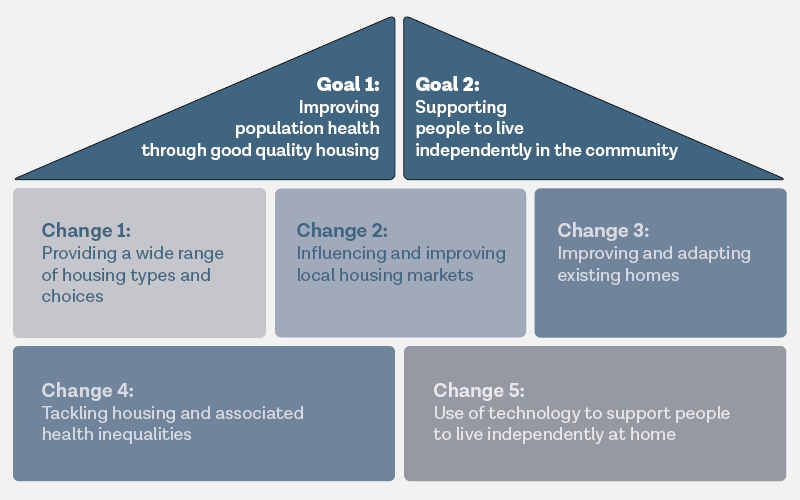

If you are in policy or senior management: Look at the High Impact Change Model, below, created by the Local Government Association/Housing LIN.

(Local Government Association/Housing LIN, 2022)

This model was developed to encourage local partners to integrate housing more closely with health and social care, identifying key housing-related actions and activities to support people to live as independently as possible. In the model’s accompanying report, each of these changes is looked at in turn. Each begins with ‘Making It Real’ statements (from Think Local Act Personal’s Making It Real Framework), tips for success to make each change, and real-world case studies to learn from.

The co-production group who looked at the ‘Living In The Place We Call Home’ theme strongly recommends this framework for senior leaders to kickstart change:

These five high-impact changes are all issues that we have touched on in our discussions. We came to them via different angles, but it’s very similar.

Further information

Read

More about the High Impact Change Model in this blog post from Housing LIN.